1 Walking

In the power dynamics of urban space, pedestrians seem to occupy a marginal position. After arriving in London and no longer driving, walking became a frequent task for me, and as a result, my perception of everyday space intensified. For example, I find myself walking a long way around a fence just to cross a patch of grass to reach a destination; navigating through the green glass shards that force me to walk on the edge of the curb; or changing paths between parked cars and construction barriers on the sidewalk. These experiences occur repeatedly under the mundane disciplines of daily life, only to be quickly forgotten. My body seems to have grown accustomed to constantly adapting to these limits, agreeing to these unspoken rules.

In Walking between the Disciplinary and the Tactical: An Embodied View of Certeau’s Everyday Practices, Maria Persu describes the act of walking as a politicized practice. “The ordinary walking people unknowingly manipulate the panoptic-spatial organizations of urban social order by selecting and recreating pathways, choosing amongst, as well as displacing, the meanings given by the dominant, institutionalized graphic representation of the city. Hidden beneath ‘the frantic mechanisms and discourses of the observational organization,’ everyday spatial practices such as walking are ways of eluding urbanistic discipline from within its terrain. According to Certeau, the minuscule trickeries of ordinary walkers represent forms of tactical resistance or anti-disciplines developed against the strategies of more powerful actors.”

2 Map/mapping

When attempting to represent the limits I encounter during daily walks, the first method that comes to mind is mapping. We often use maps to recall, understand, and navigate space. However, conventionally, maps are drawn from a bird’s-eye view, with static lines connecting static points—clearly not the way we actually perceive the world. As Tim Ingold states in The Life of Lines, ‘we perceive the world along a path of observation. As we move, things fall into and out of sight, new vistas open up, and others are closed off. Through these modulations in the array of reflected light reaching the eyes, the structure of our environment is progressively revealed. Seeing the gap between a conventional map and my need to represent a specific spacial narrative, I felt a need in shifting perspectives in mapping. Can a map envision the dynamic process along with moving and walking? Can a map speak for the path of an ordinary walk?

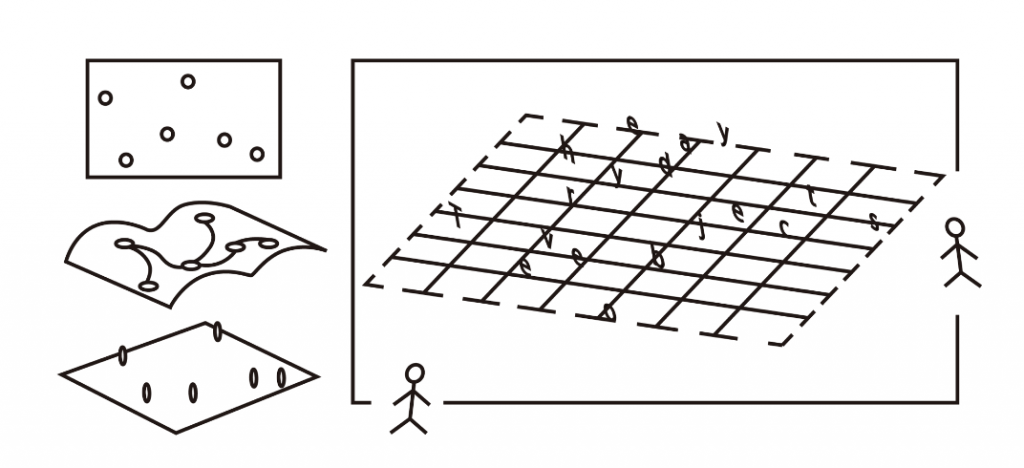

Masaki Fujihata’s multimedia work Field-work@Alsace (2002) offers a new angle to ponder on these questions. By using virtual technology to present 3D space, he links time to each participant’s movement path, transforming the map into a dynamic process of movement and redefining the relationship between maps and the body. Through this shift in perspective and medium, he encourages the audience to engage in the generation of the map and the reevaluation of how we understand maps and perceive space. In this work, time serves as a key element, transforming the conventional mapping process into a collectively constructed graphical system that allows for individual voices to emerge.

How far can we stretch the meaning of maps? We usually do not question maps and the images they provide. But if we just take a moment to think, we will recognize that maps are neither true nor natural; they are selective visual representations, translated to communicate specific information. When thinking about a contemporary map, the impression is often dominated by the virtual images constructed by platforms like Google Earth. It provides us with an illusion of wholeness. “The language of cartography is so ingrained that it has become invisible.” A set of postcards created by Clement Valla highlights the 3D rendering and data errors in Google Maps, pointing out to the audience that the images in Google Maps and Google Earth are far from perfect or objective. Does designers take the responsibility to point out that fact about maps while creating the visual system?

3 Writing

When looking at Joseph Kosuth’s work, I noticed the power of text; it eliminates distractions(the deceptive images) and cuts to the chase, prompting me to decide whether I want to engage in the meaning-making process. Given this context, I wonder if text could serve as a potential tool for resisting the conventions we have come to accept as natural in both graphic mapping systems and mundane spaces.

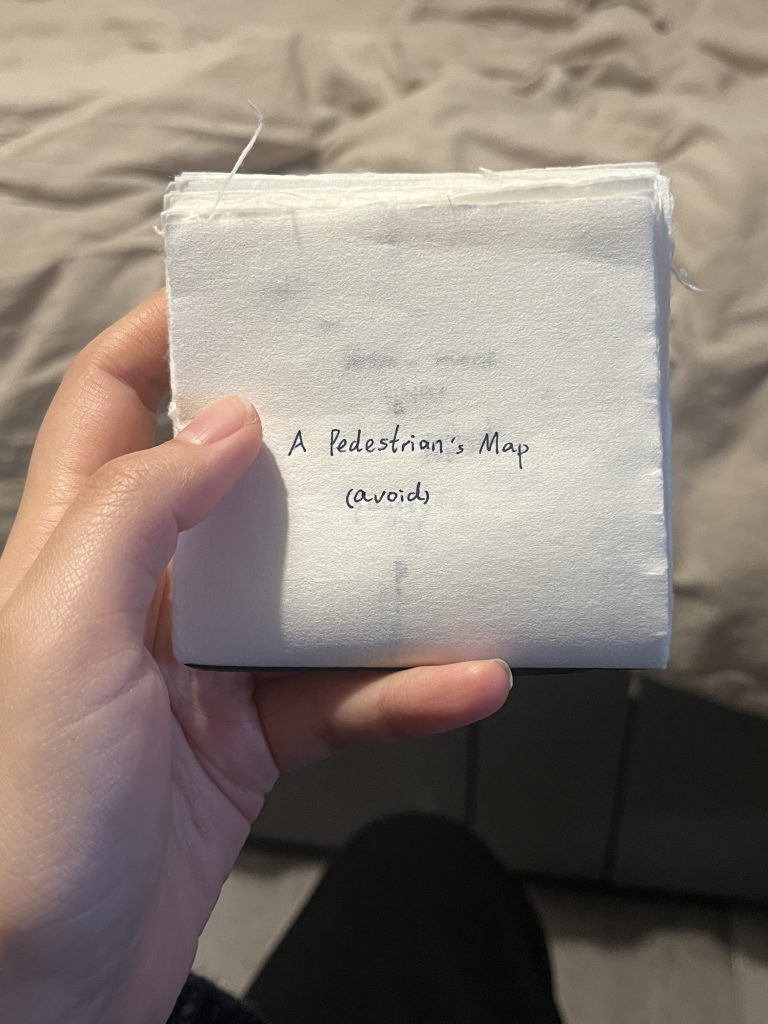

4 Visual iterations

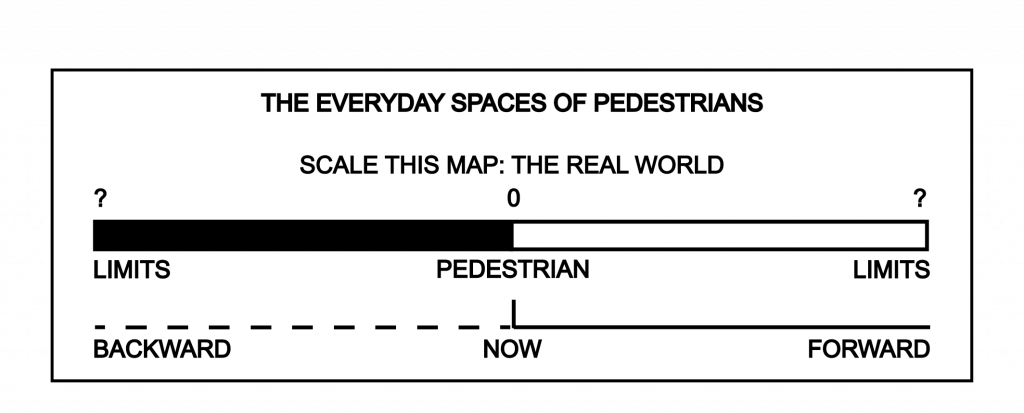

Instead of showing static distances between fixed points, I replaced the conventional elements of map scale to reverse the perspective and concept of a map.

Expanding on the idea of mapping a “path of observation and perception” in relation to “limits,” I considered using 3D space and recording movements with a camera to shift the perspective of viewing both the map and the mundane space, emphasizing how these limits shape pedestrians’ everyday paths.

As I navigated through texts in 3D space, the forward movement of the camera created an unreal sensation similar to my experiences in Google Earth, where there is no friction. This contrasts with the personal experiences I aimed to depict through mapping. Later, when I scrolling through the rendered images frame by frame, the imperfection and unsmoothness brings my attention to 2d media.

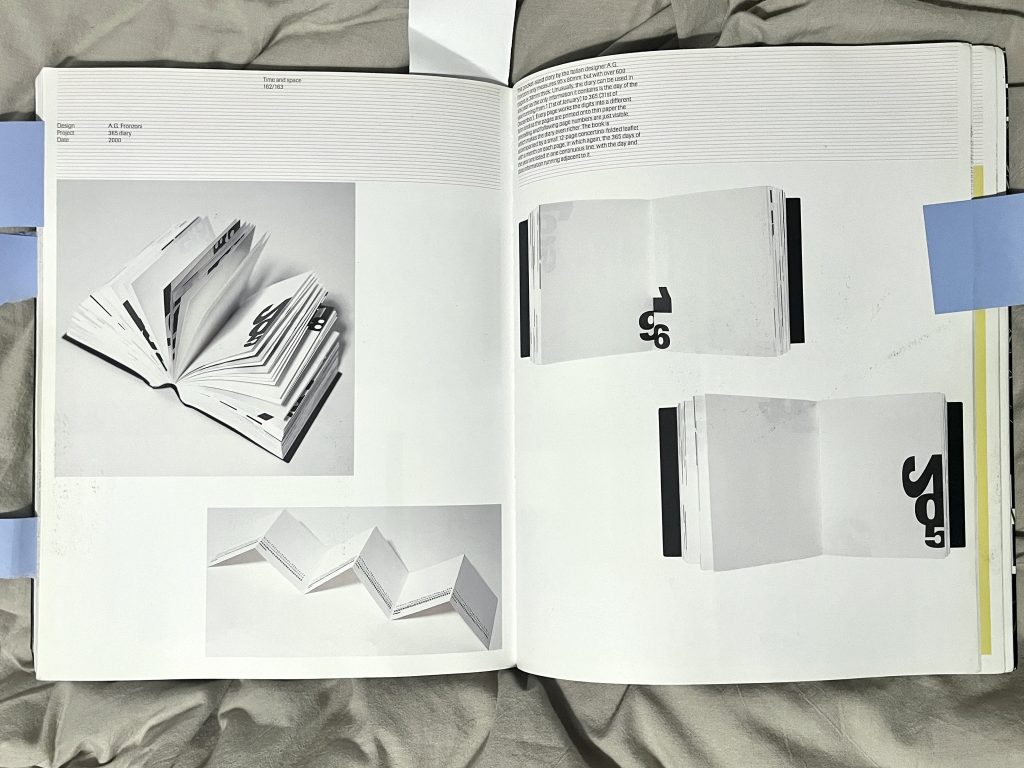

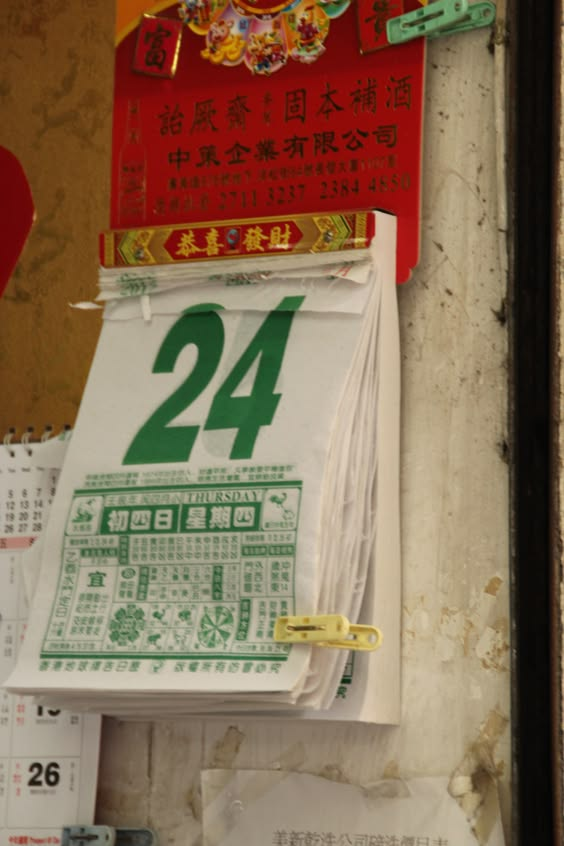

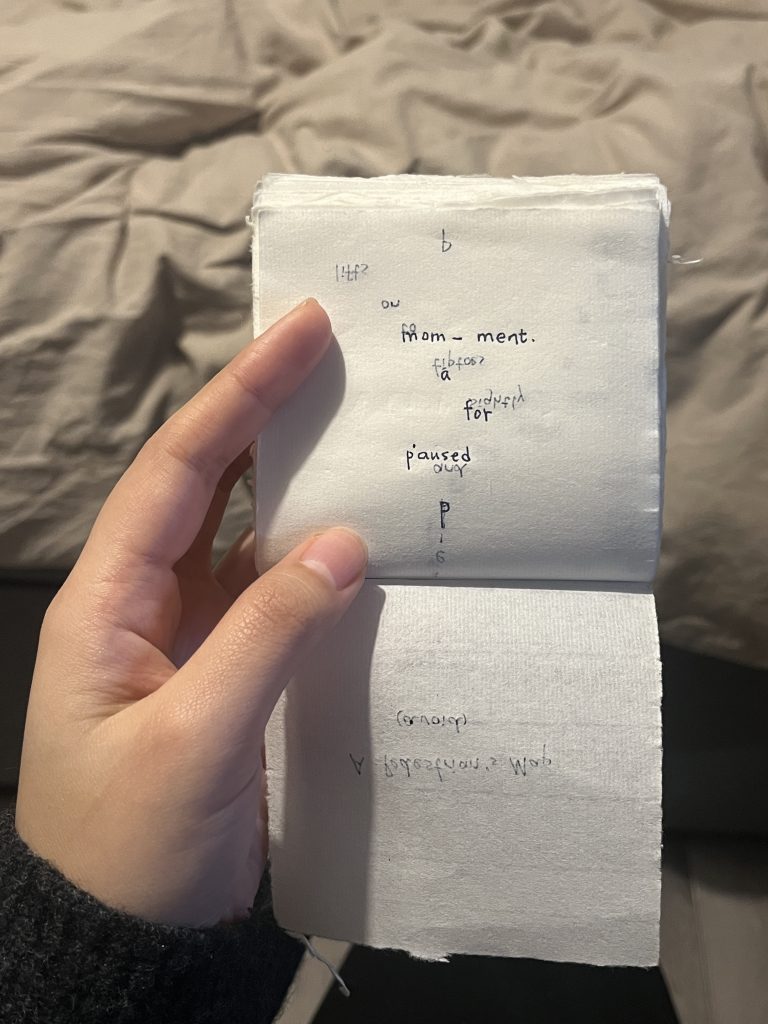

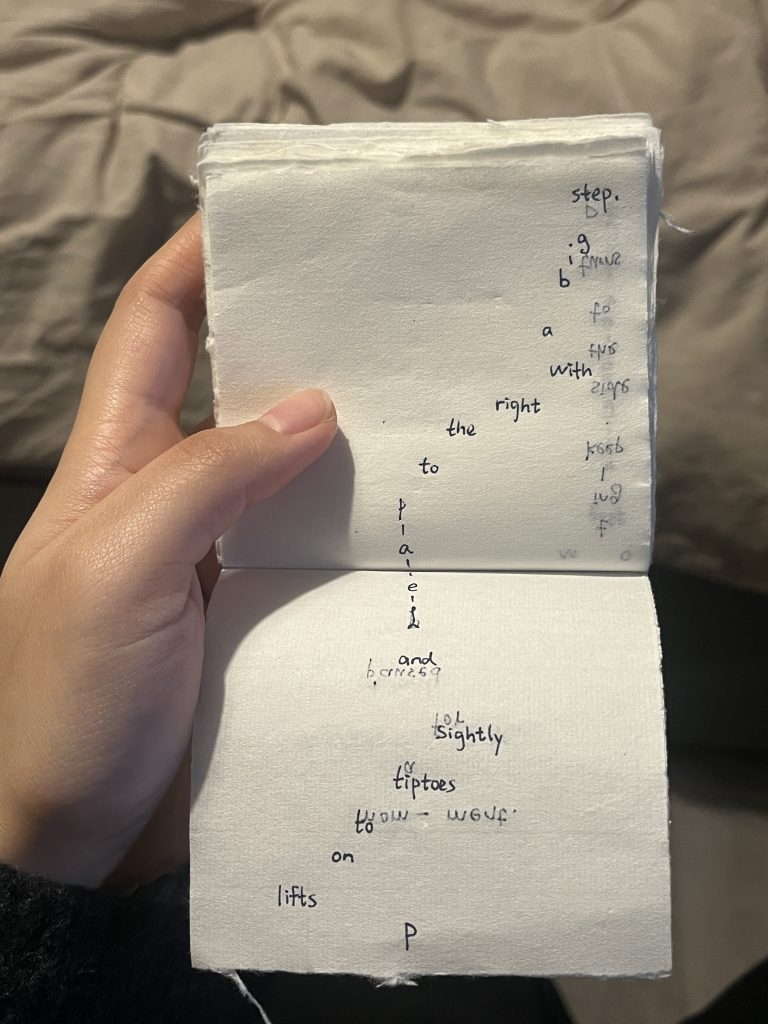

On form: Can I incorporate the element of time into a mapping system through the form of a publication? I was inspired by A.G. Fronzoni’s work 365 Diary, which made me think of an old hand-tear calendar. In this design, time is woven into the experience through the act of flipping pages and using thin paper that reveals preceding and following content, adding a sense of continuity and intimacy.

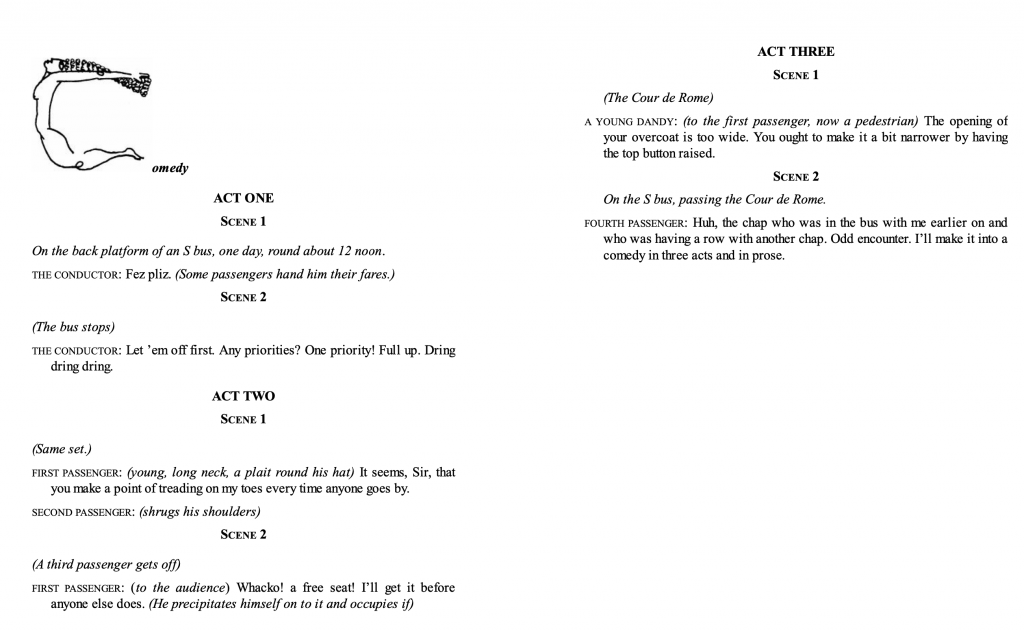

I went through Exercises in Style to get inspired and realized that a short script format could be an accessible way to connect with bodily movements. Rather than focusing on defining or naming objects, I’m considering shifting the writing to movements—such as pausing, stepping, or avoiding—to illustrate how individuals engage with and navigate mundane surroundings.

Bibliography:

Joseph Kosuth ’text/context’

Walking as research practice: A special issue resulting from the WARP conference (September 2022)

Up,across and along,The life of lines, tim ingold

Walking and Mapping: Artists as Cartographers

Mapping: An illustrated guide to graphic navigational systems

Masaki Fujihata, Field-Works

Postcards from Google Earth by Clement Valla

Exercise in style,Raymond Queneau