Further research and visual outcomes

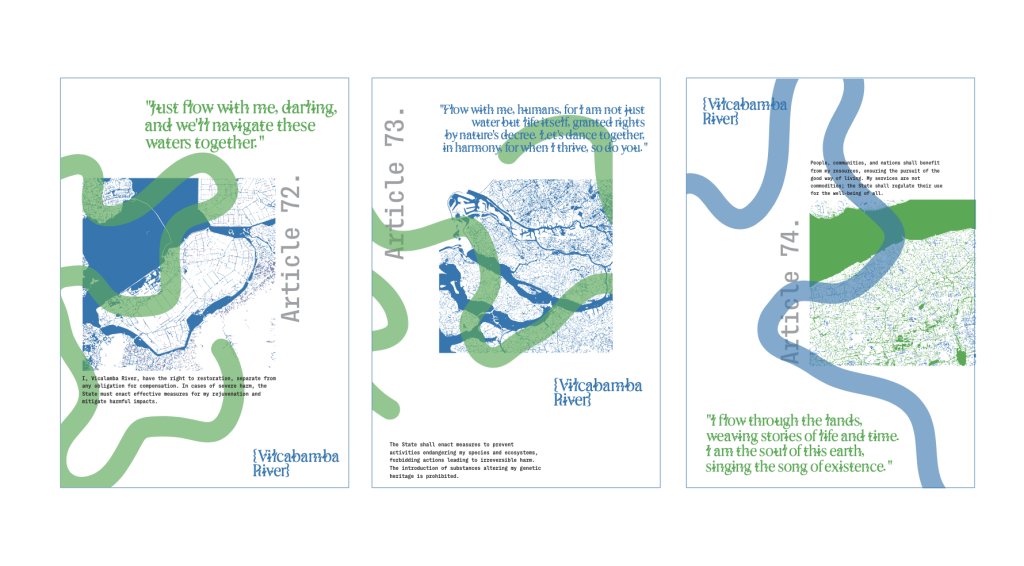

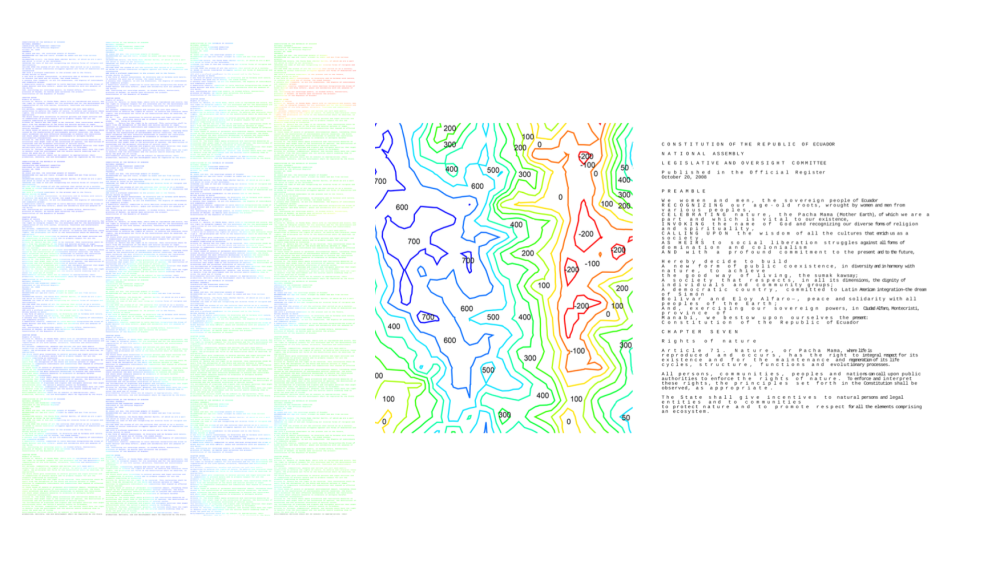

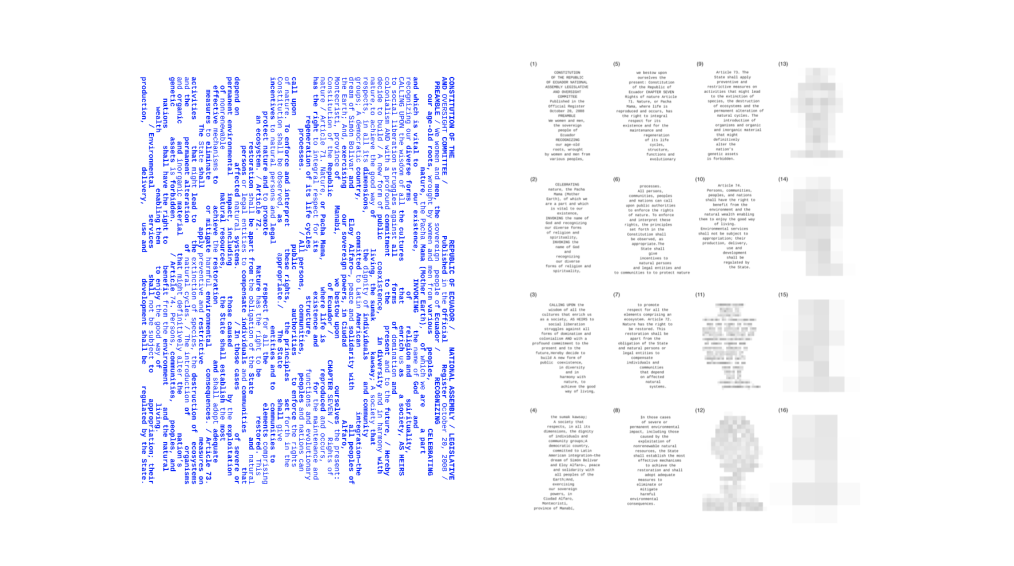

CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF ECUADOR, 2008, Chapter seven, Rights of nature

The natural environment has historically always been seen as a property with resources to be exploited. In the 1970s, the theory of giving rights to nature was first proposed by the American legal scholar Christopher D. Stone, “The history of the law suggests a parallel development…I am quite seriously proposing that we give legal rights to forests, oceans, rivers and other so-called ‘natural objects’.”[1]

The Rights of Nature movement is based on a guardianship model, meaning vulnerable non-human entities like rivers can be represented in court. On a planet that needs protecting more urgently than ever before, this new way of thinking (and acting) is gathering momentum.

“…these changes led to a rising prominence of the figure of Pachamama, the embodiment of Mother Earth in Andean myth. Also evoking a meeting of two worlds, this name is a portmanteau of pacha, the Quechua and Aymara word for “world”, and mama, the Spanish word for “mother”. Out of these circumstances soon came a wave of aspirations to endow nature with a legal status.” [2]

Rights of nature are being asserted most powerfully in post-colonial countries where there has been a tradition of indigenous communities having stewardship over the natural environments, like New Zealand and Bolivia.

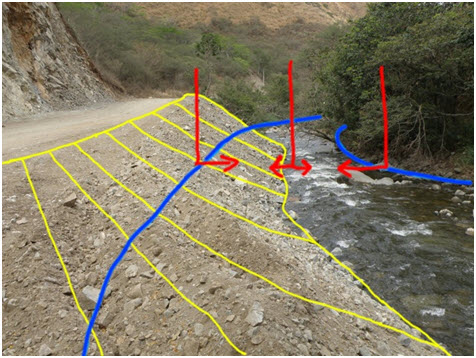

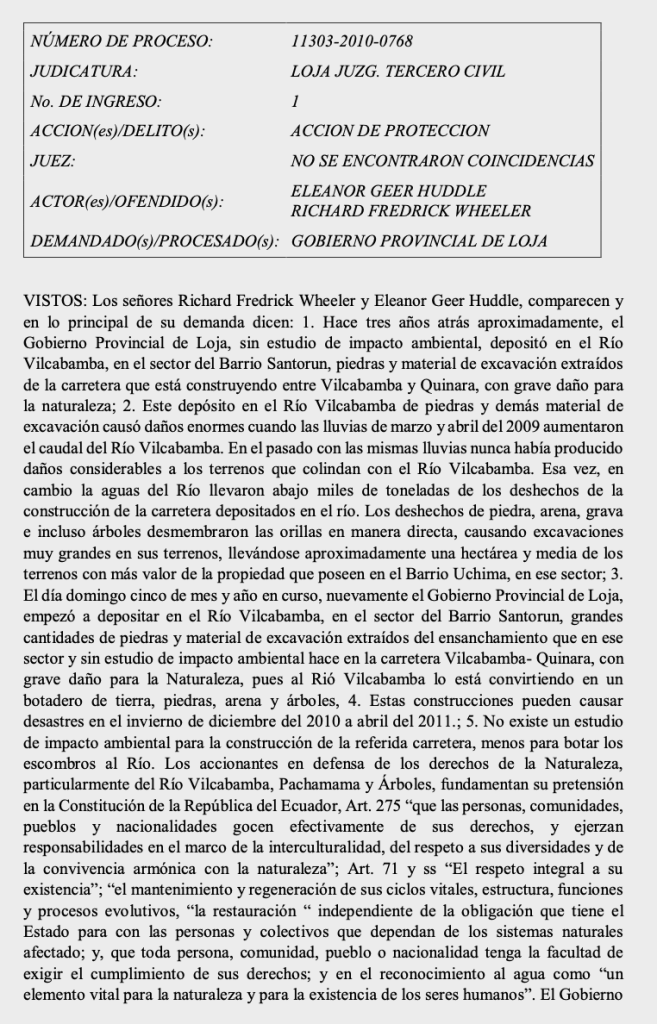

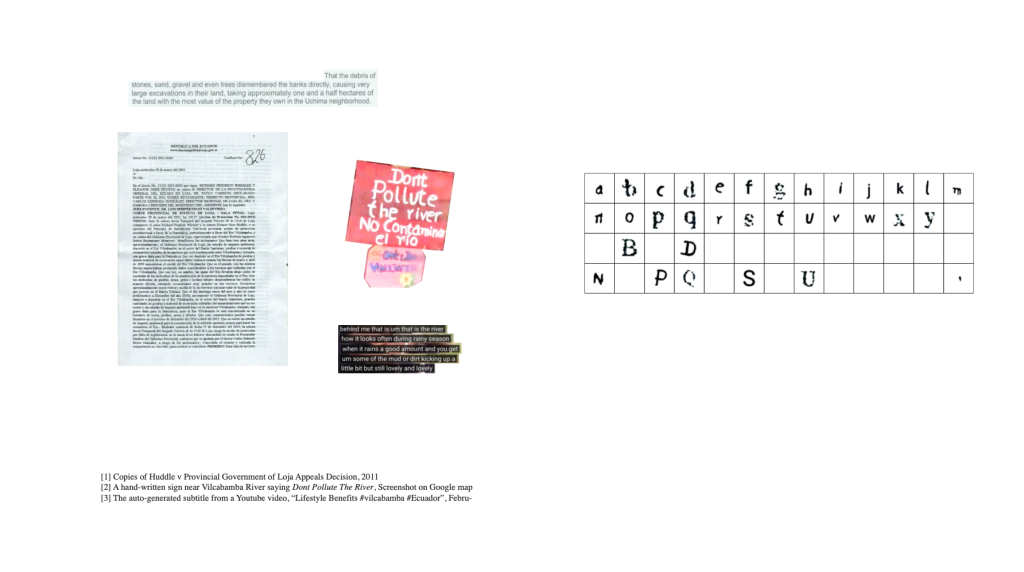

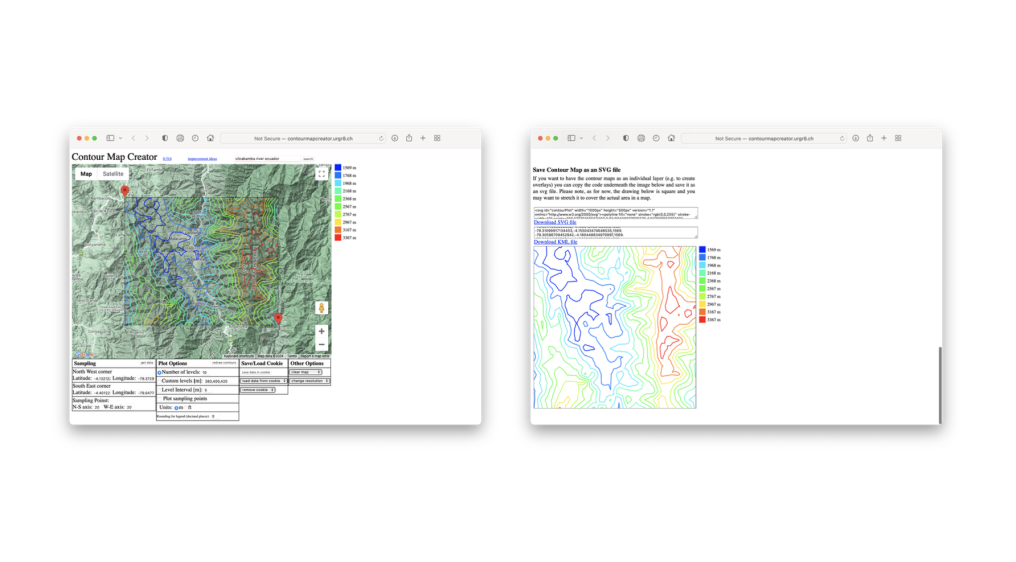

In 2010, A constitutional injunction was presented to stop a project to widen the Vilcabamba-Quinara road, which was depositing large quantities of rock and excavation material in the Vilcabamba River. The plaintiffs, Richard Frederick Wheeler and Eleanor Geer Huddle claimed that the project violated rights of nature.

In 2011, the court ruled in favor of nature and declared that the Provincial Government of Loja should have provided certain proof that the widening of the road would not affect the environment. It ordered the Provincial Government of Loja must present a remediation and rehabilitation plan of the Vilcabamba River. It also ruled the defendant must publicly apologize in the local newspaper.

Decision, 2011

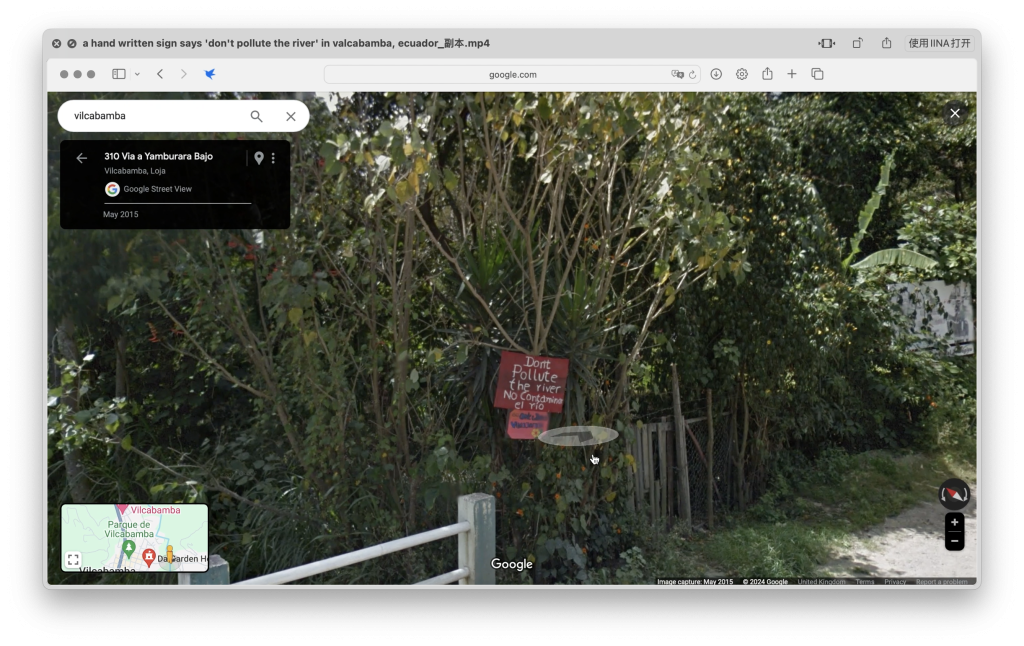

‘Don’t Pollute The River’”, Screenshot, 2024

“Lifestyle Benefits #vilcabamba #Ecuador”, February 2024

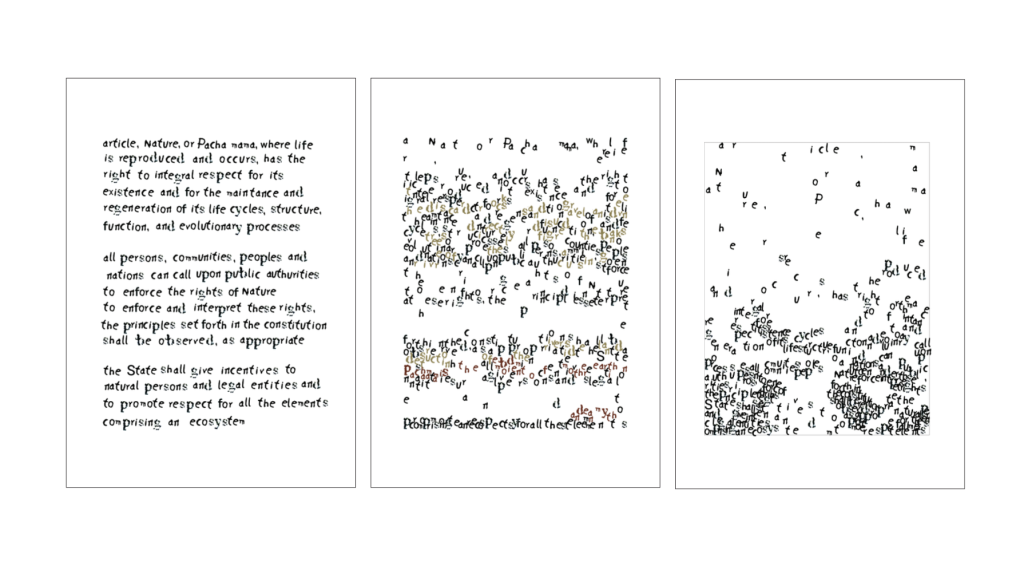

Visual outcomes

Our group members each did separate experiments based on certain common rules.

And then we combined our work together with a folder.

Reference

[1] Should trees have standing? Toward legal rights for natural objects, Christopher D. Stone, 1970

[2] ‘Legal animism’: when a river or even nature itself goes to court, Diego Landivar, 2024